Public Spatial Computing

Examples

About us

Spatial computing in public cultural institutions

Cultural institutions engage visitors in ways that can be evolved with spatial computing infrastructure—from the planning stage of exhibitions, to the richness of immersive experiences, to the external integration with digital tooling at civic or social scale.

Exhibition design and media orchestration

Spatial computing redefines how exhibitions are conceived, installed, and experienced. Instead of designing around static walls and linear timelines, curators and designers can choreograph dynamic, responsive media environments—where narrative, sound, light, and interaction flow across space in real time.

What becomes possible:

Adaptive exhibitions that change based on visitor behavior or thematic cycles

Spatial media routing that coordinates video, audio, projection, and AR content across rooms or devices

Collaborative authoring environments where curators, artists, and technologists work together in shared 3D scenes

Accessible experiences with multimodal content triggered by spatial cues or user needs

Public spatial computing allows institutions to prototype and orchestrate exhibitions as systems, not just layouts—empowering experimentation while reducing physical risk and cost.

image credit: All-Together-Now, an installation by Children of the Light. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

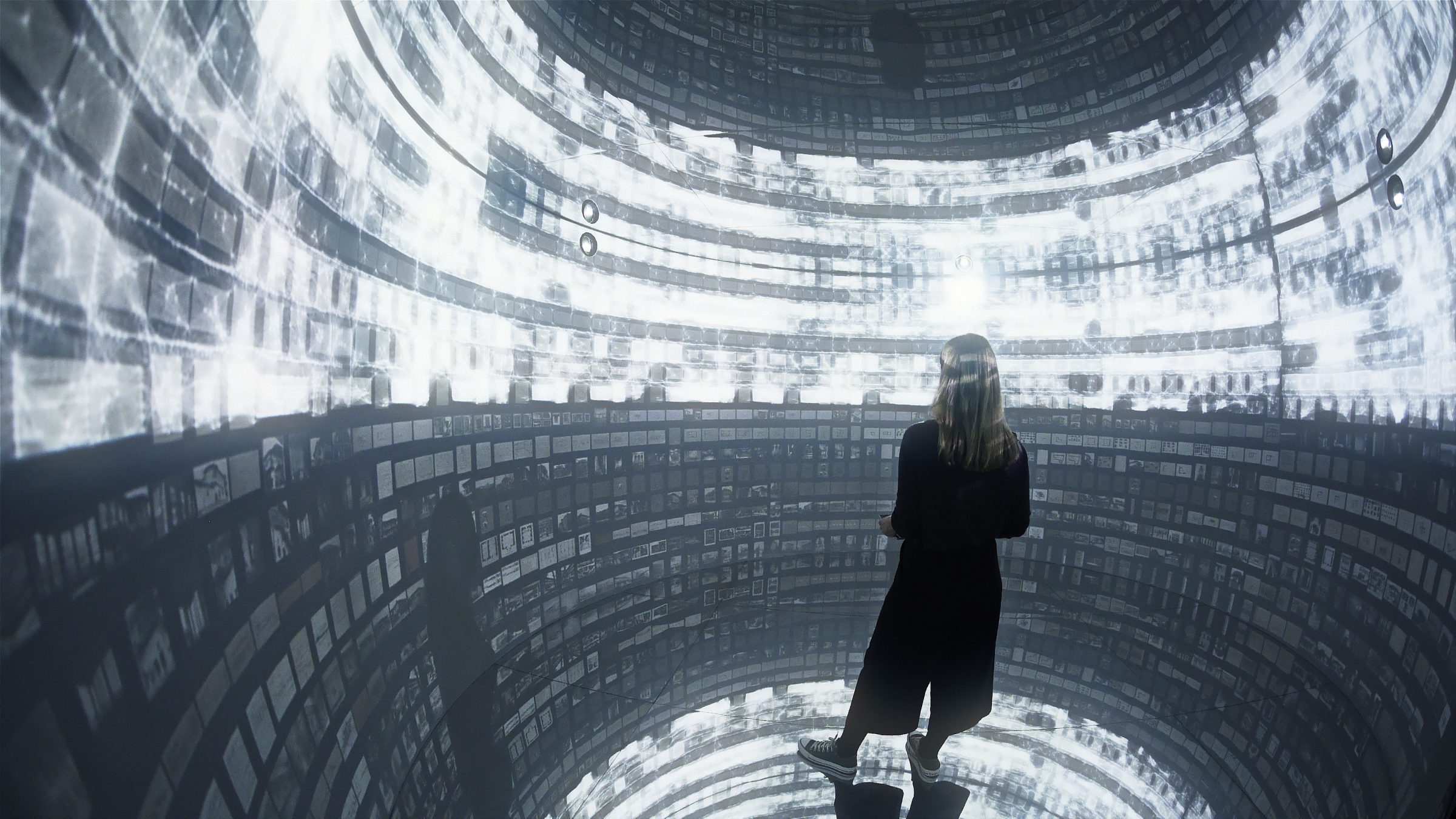

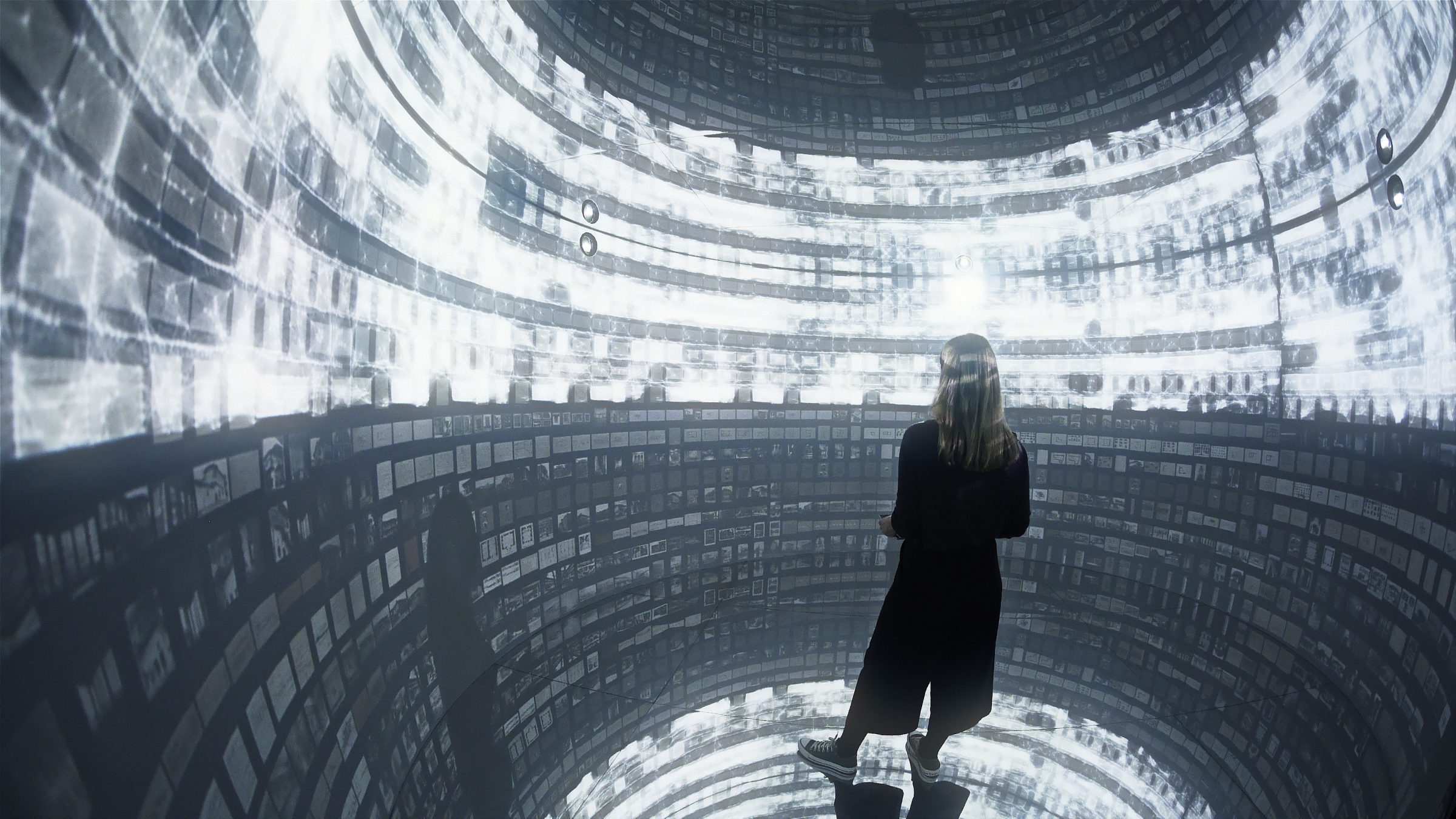

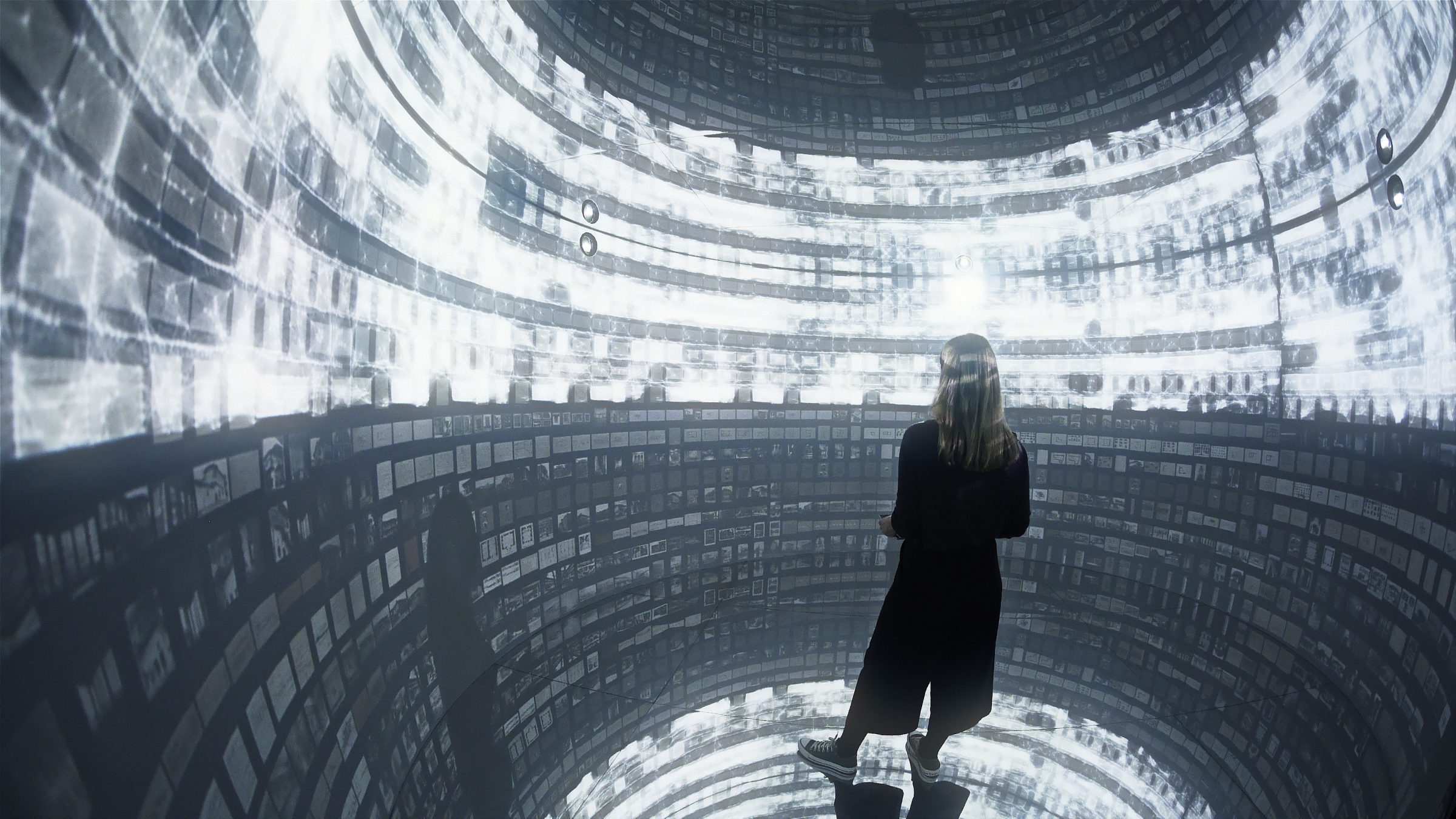

Immersive archive data visualizations

Archives are rich, but often overwhelming. Spatial computing makes it possible to step inside an archive—not metaphorically, but literally—by arranging documents, objects, and metadata into navigable 3D landscapes.

What becomes possible:

Immersive visualizations of archival collections organized by time, geography, or thematic resonance

Multisensory interfaces that reveal hidden relationships across media types

Public annotation and storytelling layers where visitors and scholars contribute perspectives in spatial context

Geolocated narratives that map archival content to real-world locations, layered with AR or digital twins

With public infrastructure, these tools can be reused and extended across institutions, giving small archives the same storytelling power as national museums—and letting the public explore history as a living, spatial terrain.

image credit: Archive Dreaming, an AI Data Sculpture by SALT Research, Google AMI, and Refik Anadol Studio. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Urban planning and cultural previsualization

Cities are constantly evolving—but most citizens can’t “see” proposals before they’re built. Spatial computing brings urban planning into public space by enabling previsualization of future developments, overlaid directly onto the built environment.

What becomes possible:

Participatory planning sessions with AR overlays showing proposed zoning, public art, or mobility changes

Immersive simulations of how traffic, climate, or public use might change under different scenarios

Cultural layer mapping, where stories, memories, or artifacts are geolocated within planning models

Cross-departmental coordination using a shared spatial interface—from transportation to housing to culture

By integrating planning and cultural data into public spatial platforms, cities can democratize foresight—making invisible systems tangible, and turning consultation into co-creation.

image credit: Ideas Study for the Lewes Station Approach, an urban planning project by Rafa Grosso Macpherson. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Public Spatial Computing

Examples

About us

Spatial computing in public cultural institutions

Cultural institutions engage visitors in ways that can be evolved with spatial computing infrastructure—from the planning stage of exhibitions, to the richness of immersive experiences, to the external integration with digital tooling at civic or social scale.

Exhibition design and media orchestration

Spatial computing redefines how exhibitions are conceived, installed, and experienced. Instead of designing around static walls and linear timelines, curators and designers can choreograph dynamic, responsive media environments—where narrative, sound, light, and interaction flow across space in real time.

What becomes possible:

Adaptive exhibitions that change based on visitor behavior or thematic cycles

Spatial media routing that coordinates video, audio, projection, and AR content across rooms or devices

Collaborative authoring environments where curators, artists, and technologists work together in shared 3D scenes

Accessible experiences with multimodal content triggered by spatial cues or user needs

Public spatial computing allows institutions to prototype and orchestrate exhibitions as systems, not just layouts—empowering experimentation while reducing physical risk and cost.

image credit: All-Together-Now, an installation by Children of the Light. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Immersive archive data visualizations

Archives are rich, but often overwhelming. Spatial computing makes it possible to step inside an archive—not metaphorically, but literally—by arranging documents, objects, and metadata into navigable 3D landscapes.

What becomes possible:

Immersive visualizations of archival collections organized by time, geography, or thematic resonance

Multisensory interfaces that reveal hidden relationships across media types

Geolocated narratives that map archival content to real-world locations, layered with AR or digital twins

Public annotation and storytelling layers where visitors and scholars contribute perspectives in spatial context

With public infrastructure, these tools can be reused and extended across institutions, giving small archives the same storytelling power as national museums—and letting the public explore history as a living, spatial terrain.

image credit: Archive Dreaming, an AI Data Sculpture by SALT Research, Google AMI, and Refik Anadol Studio. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Urban planning and cultural previsualization

Cities are constantly evolving—but most citizens can’t “see” proposals before they’re built. Spatial computing brings urban planning into public space by enabling previsualization of future developments, overlaid directly onto the built environment.

What becomes possible:

Participatory planning sessions with AR overlays showing proposed zoning, public art, or mobility changes

Immersive simulations of how traffic, climate, or public use might change under different scenarios

Cultural layer mapping, where stories, memories, or artifacts are geolocated within planning models

Cross-departmental coordination using a shared spatial interface—from transportation to housing to culture

By integrating planning and cultural data into public spatial platforms, cities can democratize foresight—making invisible systems tangible, and turning consultation into co-creation.

image credit: Ideas Study for the Lewes Station Approach, an urban planning project by Rafa Grosso Macpherson. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Public Spatial Computing

Examples

About us

Spatial computing in public cultural institutions

Cultural institutions engage visitors in ways that can be evolved with spatial computing infrastructure—from the planning stage of exhibitions, to the richness of immersive experiences, to the external integration with digital tooling at civic or social scale.

Exhibition design and media orchestration

Spatial computing redefines how exhibitions are conceived, installed, and experienced. Instead of designing around static walls and linear timelines, curators and designers can choreograph dynamic, responsive media environments—where narrative, sound, light, and interaction flow across space in real time.

What becomes possible:

Adaptive exhibitions that change based on visitor behavior or thematic cycles

Spatial media routing that coordinates video, audio, projection, and AR content across rooms or devices

Collaborative authoring environments where curators, artists, and technologists work together in shared 3D scenes

Accessible experiences with multimodal content triggered by spatial cues or user needs

Public spatial computing allows institutions to prototype and orchestrate exhibitions as systems, not just layouts—empowering experimentation while reducing physical risk and cost.

image credit: All-Together-Now, an installation by Children of the Light. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Immersive archive data visualizations

Archives are rich, but often overwhelming. Spatial computing makes it possible to step inside an archive—not metaphorically, but literally—by arranging documents, objects, and metadata into navigable 3D landscapes.

What becomes possible:

Immersive visualizations of archival collections organized by time, geography, or thematic resonance

Multisensory interfaces that reveal hidden relationships across media types

Public annotation and storytelling layers where visitors and scholars contribute perspectives in spatial context

Geolocated narratives that map archival content to real-world locations, layered with AR or digital twins

With public infrastructure, these tools can be reused and extended across institutions, giving small archives the same storytelling power as national museums—and letting the public explore history as a living, spatial terrain.

image credit: Archive Dreaming, an AI Data Sculpture by SALT Research, Google AMI, and Refik Anadol Studio. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.

Urban planning and cultural previsualization

Cities are constantly evolving—but most citizens can’t “see” proposals before they’re built. Spatial computing brings urban planning into public space by enabling previsualization of future developments, overlaid directly onto the built environment.

What becomes possible:

Participatory planning sessions with AR overlays showing proposed zoning, public art, or mobility changes

Immersive simulations of how traffic, climate, or public use might change under different scenarios

Cultural layer mapping, where stories, memories, or artifacts are geolocated within planning models

Cross-departmental coordination using a shared spatial interface—from transportation to housing to culture

By integrating planning and cultural data into public spatial platforms, cities can democratize foresight—making invisible systems tangible, and turning consultation into co-creation.

image credit: Ideas Study for the Lewes Station Approach, an urban planning project by Rafa Grosso Macpherson. Work unaffiliated with Spacecraft.